Prose

Contents:

Fiction

Since August (November 24, 2020)

the sodium-yellow light shining for the sake of the dumpster hasn’t gone out. It was a prick in the veil of the night when I attended to my errands (nearly busted my knee from an erect edge of pavement), but felt brash enough to come back out when I no longer needed it.

Since August the main door to the building my apartment is packed in has never been locked. Going out for groceries, I found a note in aggressive, thick Sharpie: “NO MAIL DELIVERED IF YOU LOCK THIS DOOR.” I was never given the key for this door. I suspect this was planned to make me rush in fear and forget to pick up chickpeas.

Criticism

Section spéciale movie review

Though on the surface it seems in line with the Costa-Gavras MO (inhumanity masked by bureaucracy, the liberation of the human spirit smothered by the excesses of bourgeois striving), Section Spéciale does deviate from form in several interesting ways. It's certainly his least revolutionary of the films I've seen (Z, État de siège, L'aveu).

The opening is unlike anything I can recall him filming: a very soft lens, flaring blue lights, continuing not just through the opera, but long into the formation of the special court. In fact, the first establishing shot that really takes the camera out of this mode is the brown and grey exterior on the morning of the trial. Whereas in other films, the revolutionary and the bureaucratic subjects are filmed distinctly (the former lively, hasty, the latter as documentary), the conspirators-turned-hesitant-assassins are shot in the same springtime colors as the ministers. Despite the more pastoral look, the film does a better job than the others of showing the excesses that pervade the state apparatus, and this is treated as an object of disgust. Not only does the process take place in baroquely decorated offices (unlike the typically austere furnishing), we are disgusted as we tour the ministers, interrupting their relaxation to be summoned.

Unlike the politics of previous pictures, there is a third subject: the convicted. Even though many of them are communists, it's clear they are distinct from the communists in the beginning of the film. Like I noted, they are introduced with a grittier camera, but they also are given a more phrenetic pacing. The edit cuts from show trial to real trial to arrest back to the first trial and finally lands at the present. The transfer of information across the chamber where the accused sit is fast and its close-ups are heartbreaking and empathetic. We see an entire life punctuated by recidivism, a love unbound by the law. The camera tracking repeats itself as the second lawyer tries to assure the second defendant. My final word on the politics is to make note of the two who most fervently react against the new law: Cournet (the first candidate to be president of the special court) and Linais (the judge who first opposes the death penalty). The former was chosen because he is politically active, the latter because he is a nationalist. The rest of the functionaries are either military veterans, or have a seat ready for them a few rungs above their current station. Costa-Gavras tells us the dangerous enemy is not the ideologue, but the man with a stamp in his hand and a wife cooking him dinner when he comes home.

TÁR moview review

TÁR is about a lot of things, and it chooses to not dwell on any of them for very long. TÁR is about a woman with a trillion affairs who never has sex. TÁR is about the managerial class and alienation from craft. TÁR is about a woman with fifty houses. TÁR is about the most self-aware narcissist too lazy to change the parts of herself that she knows are horrible. In a normally-structured movie, I would say this next point is the most important point, but this is not a normally-structured movie: TÁR is about the grain of sand a few centimeters above the high tide mark, on an unstable equilibrium. Any perturbation could topple it backwards just a hair, and the next time the tide comes in, it'll be washed into the turbulence. So what?

The film starts out really strong, on what I can describe best as the "atheist marxist professor/Christian veteran student" copypasta that was popular on facebook about a decade ago. Sadly, TÁR isn't very original in this respect (even if it does invert the student and the teacher's identities), taking cues from the seminal 2014 film God's Not Dead (dir. Harold Cronk). Despite my sarcasm, I do have to give some credit for having a good feel for the times--it's a pretty accurate portrayal of the fears and hysterias that are popularly felt at the moment. The line "She shipped herself to equatorial Africa and canoed up the Congo River to track Schweitzer down" gave me the same feeling as reading "The Part about the Critics" in Roberto Bolaño's 2666. It's hard for me to tell what the intentions of the filmmaker were with this dialogue (a running theme in this movie (I take this value-neutral, I don't have any reservations about ambiguity)). I also couldn't help myself from comparing her ethos to Godard's King Lear. My reading of his King Lear is that creativity can emerge from anything. To summarize and expand on my review of that movie, the double take of the first scene in King Lear is the scene that shows this. From a single mote, a single scene redone, we see differences in cadence, in posture, in light, in method. The number two emerges from the number one! Even further, when you think about the plot--nuclear apocalypse has erased human cultural history--the human project doesn't end, it emerges anew, with all the same sorts of flaws and imperfections that the old one had, even if they are different in their exact nature. Lydia Tár's idea of creativity starts and stops at the page, and it might even be more constrained than that. Some works of art are not worthy of performance because they require too much effort to extract meaning from. Again, this is directed mostly towards the fictional character, though now it's time to be catty and say that, considering the depths of creativity the camera effuses, I think there are some Tár particles in the filmmaker.

There's a real disgust with audiences and musicians in the movie. The trumpet player moved off-stage. During the New Yorker interview, after the applause at the beginning, the next time we really hear the audience is the laughter after hearing the foot-stabbing and gangrene. One of the scenes when we hear her play the most music is to be petty and cruel. Like I said in the preamble, alienation from craft. PMC. Creativity is an object of repulsion. The world, through the lens of TÁR is to be tamed.

To be empathetic, I do understand this. I have some degree of noise sensitivity. Last year I lost countless hours of sleep because of my downstairs neighbor's penchant for composing his own drum sequences starting at 11pm and, when he was feeling generous, ending at 1:30 am. Several years before this, I invested in ear plugs because the chatter in the five minutes before college lectures started was unbearable. I know, not just looking back, but I knew at the time how obnoxious this air was. Noise is of the world, and noises are not produced on their own. If you have this (truly neurological) reaction to noise, it's pretty easy and convenient to try to completely isolate yourself from that which produces it. Of course the noise-maker is the world and you can't isolate yourself from the world for long before it crushes you. This is what I find truly beautiful about the ending of TÁR. Succumb to the world. Betray your learned impulse of bourgeois striving. It is unhealthy. It doesn't make you feel good.

I wish I could end this with a recommendation for some real gnarly atonal piece, but to be frank, I don't listen to atonal music all that often. Nothing against it. I would like to recommend, as I do so often that it feels contrived, Tetsu Inoue's World Receiver. Since it's starting to feel contrived, I'll give a reason. The opening song starts in the midst of a crowd. For some occulted reason related to brain development and childhood experience, I always picture this as a food court in a mall. It's busy, but I've never found it overwhelming. The way Tetsu Inoue mixes his sound sources always gives me the space to breath and examine each with the respect they deserve, all at once. It's a lesson that I've held dear and always try to take with me outside of my apartment, into the vast, uncontrollable world of sounds.

Tetsu Inoue - World Receiver: www.youtube.com/watch?v=grlYRK1aSus

The Pequod is Haunted

Whalers (c. 1845) - J.M.W. Turner via The Met (public domain)

Many spirits are lingering about the deck of the Pequod.

Publically-Funded Avant-Garde

IRCAM, Spectralism, Technology, and Art

Journal excerpts

Do you think of them? (April 18, 2021)

The archeologists, historians, and archivists who’ll dream-in-eyes seek out the past only to find the detritus you and I have left behind?

I hope our mess will be foreign to them not in the issue of translation but in ways of living.

Two entries in series

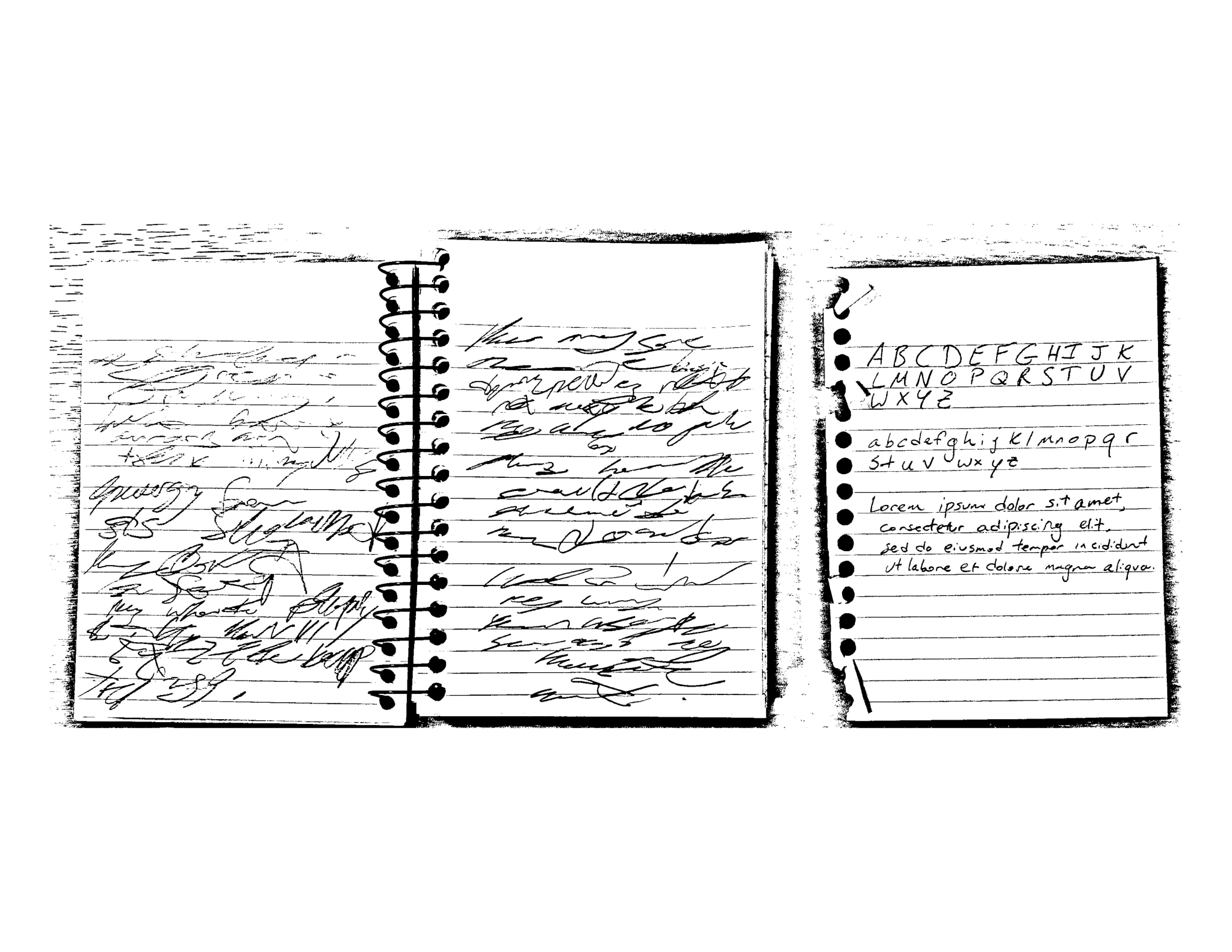

August 23, 2020: I’m writing a book titled “Making Sense of the Text.” [The following 324 pages consist of incoherent rambling.]

November 7, 2020: Three months to think, and this line is all I’ve come up with.